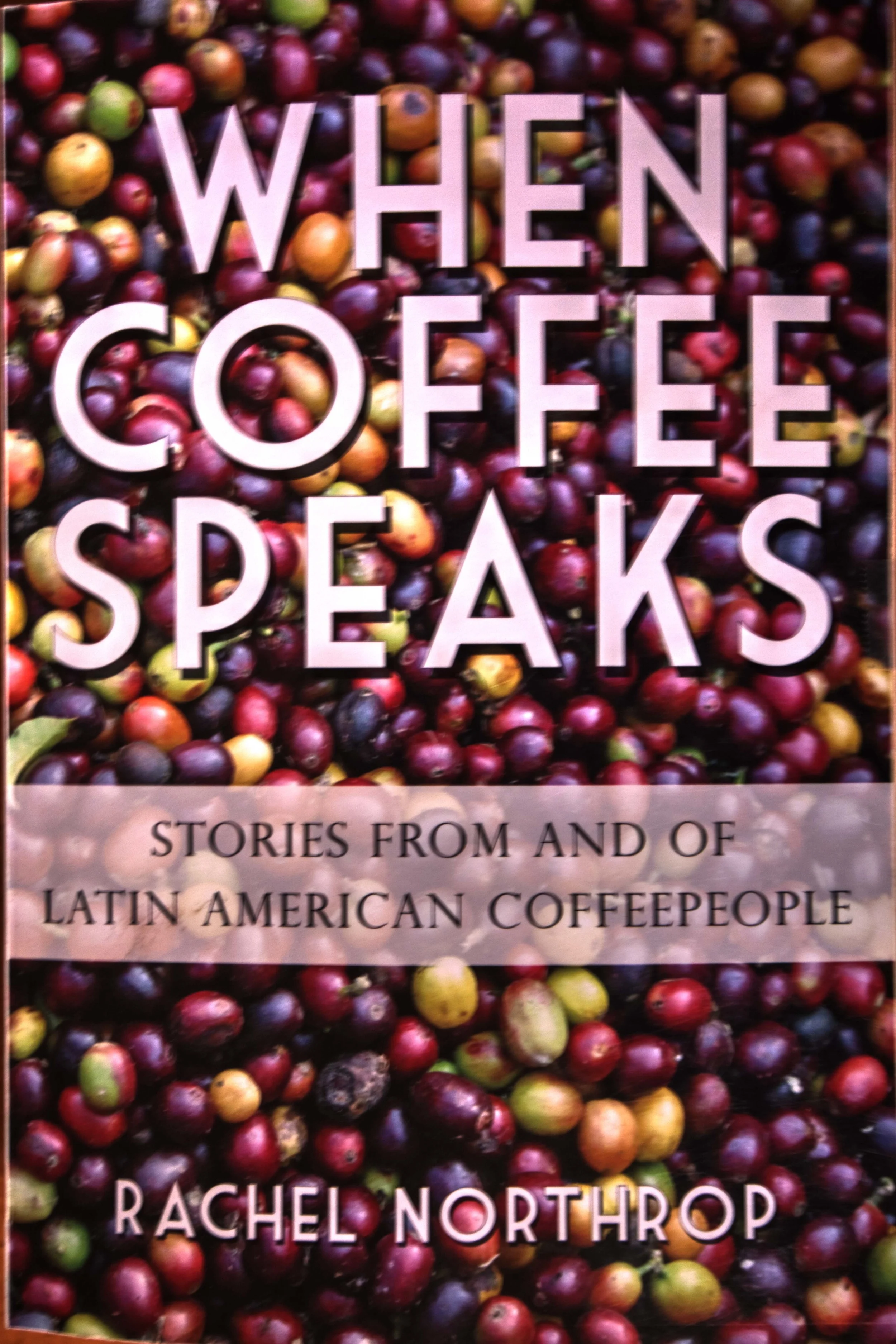

I’ve been reading When Coffee Speaks by Rachel Northrop.

To call the book entertaining and educational is an understatement. For a year, Rachel recorded conversations with coffee farmers, their families, agronomists, exporters, millers, shop owners, roasters, coffee scientists –to compile a rich, complex tapestry of life in coffee. If coffee was taught in college this would be a must read textbook – and it reads smoothly and is vastly entertaining.

The book is a window into a cross section of all aspects of coffee production throughout Latin America. It is a story of coffee farmers, in their words, of the challenges and triumphs over generations of working the land. Overwhelmingly it is a story of what connects these families to the land and what sustains them for generation after generation.

The interviews are short – one or two pages – that leaves the reader wanting more. But it is through these short conversations, over time and geography that the picture emerges.

As a former coffee buyer and roaster I’ve always been fascinated by the weights and measures of coffee. The way that the terminology and methodology of processing changes from country to country. It is as fascinating as it is confusing. Fanegas, quintales, cahas, ladas, manzanas, hectares, cuerdas; are we talking about coffee cherry before processing, parchment coffee with the pulp removed or “oro” – green finished coffee ready for sale. When you have conversations with producers its helpful to know what is being talked about. This book will give the coffee professional a thorough foundation on the language of coffee and for the consumer one comes away with a practical picture of the realities of what it takes to bring that coffee to our table.

Here is Guido, a co-op member and organizer from Costa Rica:

“ ….another problem is the fall of international coffee prices. In Costa Rica, to produce a fanega(about 550 lbs of coffee cherry) costs us 50-55000 colones, so that’d be $100-$110. The advances are at maximum $80. And from that we have to pay the harvesting, the transportation, and we have to pay the people who financed us to be able to maintain the farm during the year. We see that the problem for farmers – it’s the same all over the world-…it’s always the same problems of high costs of production, of chemical and fertilizer inputs, of fuel. That and changes in climate. Because we don’t produce, we induce nature to produce for us.” pgs 87-89

Here's another excerpt:

Rodolfo, a manager of a coffee mill in Costa Rica “You asked me how I started in coffee. I’ll tell that my whole life is coffee. First, starting at seven years old, I went to the cafetales (fincas, coffee farms) to pick coffee. I was able to go to school thanks to the coffee harvest. When school was out, I’d spend the two months off, December and January, picking coffee to save money to keep studying. And that’s how it is with all the families around here. Coffee is a difficult crop to cultivate, one with many processes. There are lots of hands involved so that you can drink a cup of coffee in the United States. It passes through so many hands!”

Rachel: "Of all the things you've done, what was the biggest challenge you encountered?"

Rodolfo: "Well, to answer that I'll speak as a produce, because I'm also a producer. It's difficult. Very difficult. Because what a producer receives is very little. In the chain of coffee, most of the money is at the top. And the ones who produce are the ones who receive the least. It's very hard. It costs them a lot of money and effort to produce, and the pay is very little. That's the most difficult part." pgs 69-70